Abstract

From mythology to science fiction, human beings have always told stories. Due to major advancements in technology during the last century, cinematography has become one of the most prominent forms of storytelling, with content ranging from real world documentaries to highly imaginative tales.

All types of fiction invite their audience to explore real ideas, issues, or possibilities using an imaginary setting or using something similar to reality, though still distinct from it. In this project, we want to extract movies that fall in the category “speculative fiction” as defined in Wikipedia [1], to distill the content of people’s imaginations and their evolution over time. Were robots and android topics more popular before technological advances made them less fictional? Were there more aliens and space movies when the first space missions occurred? Those are questions we will try to answer in this Data story.

Fictional movies

A bag of fictional movies

The first goal is to get a subset of fictional movies and their summaries. The main information we get to classify movies as fictional and non-fictional is their genres given by the CMU dataset. Let’s have a look at the genre’s distribution. In the CMU dataset, movies can be associated with several genres in no particular order of importance. There are more than 300 hundred different genres. The graphs below shows the proportion of movies taken in account by selecting only a given number of genres.

We can see that the 40 most represented genres cover more than 80% of the whole movie dataset! Among these 40 selected genres, science fiction and fantasy were chosen as the only ones clearly associated with fiction. This gives us a first subset of 5366 fictional movies corresponding to 6.56% of the whole movies But wait, is this subset representative of all the fiction pieces released during the last 100 years? Several biases can be highlighted. First, our subset depends on the classification people made for movie genres. Then, do we miss many fictional movies by selecting only SF and Fantasy movies? Aren’t there other minor fictional genres? Aren’t there hidden fictional movies, only classified for example as drama or action?

To try to mitigate these biases, we use the IMDB genres classification. We selected all the movies classified as SF and Fantasy and merged them with the CMU dataset. In this way a larger part of the CMU movies is integrated in our fictional movies’ subset. It now contains all movies classified as SF and Fantasy by CMU or IMDB (ie. 6506 fictional movies corresponding to 7,9 % of the whole movies)

Fictional worlds but from which part of the world?

We want to capture people’s imagination through fiction. But which people’s imagination are we trying to decode? The graph below shows where the movies of our fiction subset have been produced. The proportion of all films produced in each country is also displayed.

Our dataset only rounds a small fraction of the films released, which must not be representative of the real bunch of films distributed each year in the world. Even if this is the case, it’s good to notice that American films will still have a greater weight in our study than films from any other country.

Time dimension

Our main object of study is to analyze the evolution of fictional worlds over time. Therefore, our fictional movies dataset must contain enough films released over the entire study period. Below is showed the number of movie releases per year.

In recent years, there have been many more films released. The possible threat this it can pose is that topics of recent films will overwhelm those of older films because they are much more represented in the data. In the rest of our story, you’ll discover how we’ve tried navigating the pitfalls and paint a picture of the evolution of the fictional worlds that have accompanied us over the last 100 years.

Detecting Fictional topics

To detect fictional topics, we used a Latent Dirichlet allocation (LDA) on movie summaries.

Topic modeling on the fictional subset

In LDA method summaries are bags of words and each topic is a probability distribution over words. Several manipulations were performed on the summaries in order to optimize the topic detection by keeping the words that carry the most information.

- Word normalization with lemmatization to gather words with close meanings

- Stop words removal

- Proper nouns removal but keeping locations, events, dates

- Non weighted words (ie : A word that appears many times in a summary won’t have a bigger weight than one which just appears one time.)

This gives us a preprocessed substed of fictional summaries.

Two LDA parameters have been adjusted to consider a low number of topics per document and a low number of words per topic.

A bias research ?

-

Number of releases : As we saw before our subset is mainly composed of recent movies that can prevent

-

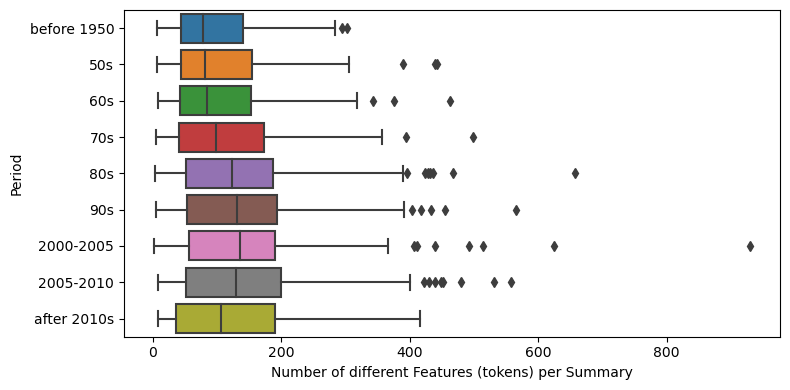

Summaries length : Summaries with a lot of words will give more weight to minor topics that may be not relevant for our study. The graph below shows the average number of words in preprocessed summaries over time . After 1950, the mean number of words in the preprocessed summaries is more stable with a slight increase and variation of around 30 words.

Finally, our subset isn’t perfect but by performing an LDA on it, we obtain the following results.

What (interesting) results !

Some fictional themes clearly stand out while others are more random. Regarding the random process of the LDA method, it is very likely that some fictional topics remain hidden.

Topics over time

We have a first idea of what fictional worlds look like. But how have they evolved ? Have any of them disappeared?

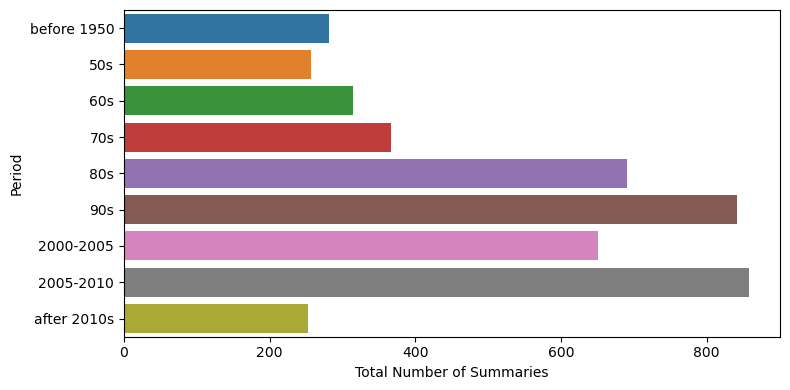

Time is split in periods where the number of movies is comparable.

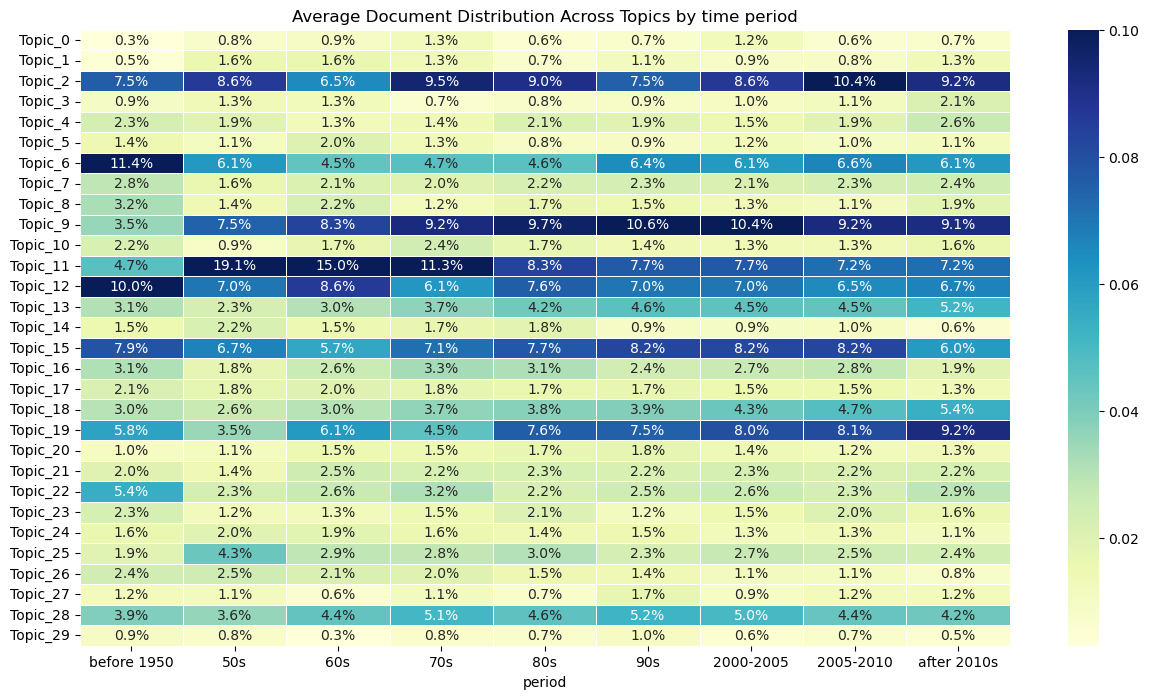

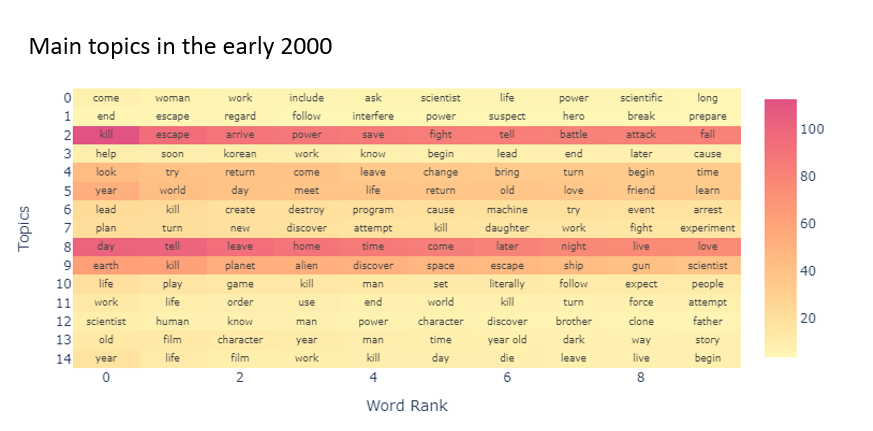

The above heatmap shows some interesting results. We can spot trends for some fictional topics.

-

Topic 11 (Earth, space, ship, planet, alien, destroy, earth earth, discover, crew, land) which we could name outer space has a peak in the 50’s and 60’s. It corresponds exactly to the beginning of space exploration (1947 : first animal in space, 1961 : first human spaceflight, 1969:First human on the moon).

-

Topic 10 (Scientist, experiment, mad, laboratory, lab, human, create, body) shows a clear decrease over the years.

In our first LDA topic modeling, all movies were considered which come with the mentioned biases. Detected topics are those corresponding to the most recent movies.

To have a better idea of the evolution of topics over time, the first idea was to perform an LDA topic modeling for each defined period. The set of preprocessed fictional summaries is split in the different periods of time. Number of tokens per summary normalization resulting from it is pretty satisfying as shown on the graph below.

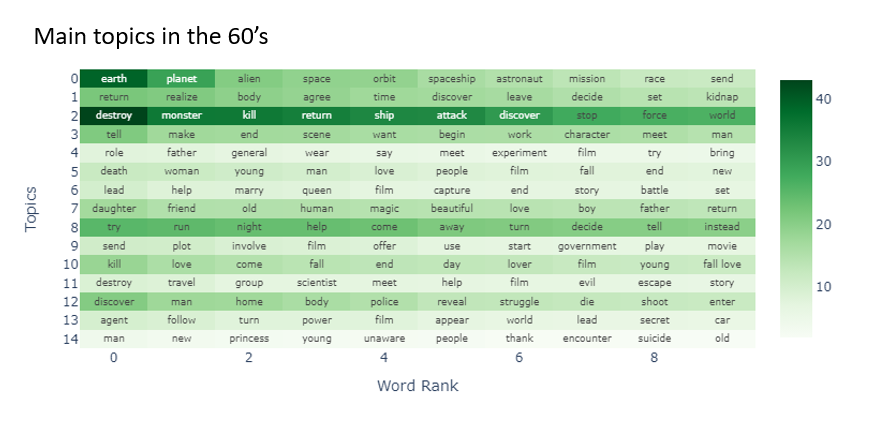

Here are the results for 2 periods.

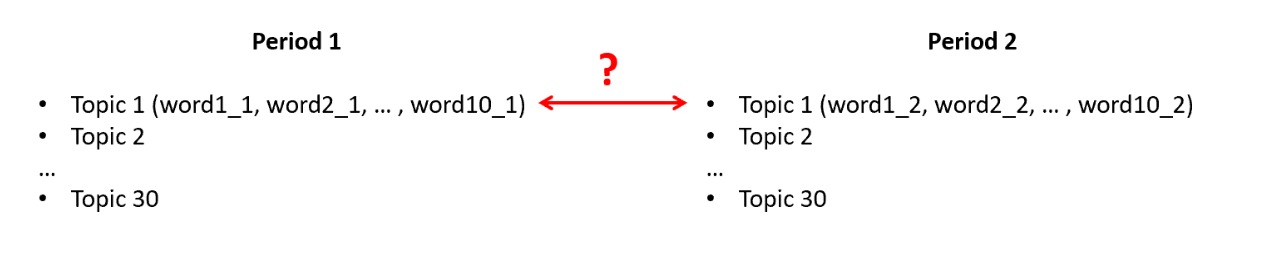

This is nice but returned topics for each period are different(ie:different word distribution) and it is tricky to link topics over different periods.

LDA topics are not clearly defined (words inconsistency in topics and topics mixing) and we probably miss some topics, eclipsed by bigger ones. However, LDA topic modeling helped us to spot fictional topics and some trends in the evolution over time.

To focus our analysis, we now define the topics that we consider to be relevant ourselves based on the LDA results.

Topic key words

| Themes | Related Keywords |

|---|---|

| Outer Space | alien, UFO, extraterrestrial, space, spaceship, outerspace |

| Science | scientist, science, researcher, research, experiment, experimentation, laboratory |

| Government | government, society, politics, regime, council |

| Creatures | creatures, monsters, vampires |

| Robots | robot, droid, cyborg |

| Digital | computer, artificial intelligence, cyber, virtual reality, cyberspace, programmer, hacking, digital |

| Magic | magic, sorcerer, wizard, witchcraft, spell, enchantment, sorcery, witch, mage, mystical |

| War | war, battle, conflict, combat, military, army, warfare, soldier |

| Time Travel | time travel, travel time, temporal displacement, time dilation, time machine, temporal journey, time loop, time manipulation, temporal paradox, time warp |

| Apocalypse | apocalypse, doomsday, end world, world end, armageddon, post-apocalyptic, apocalyptic, cataclysm, world destruction, human extinction, mass extinction, end of civilization |

As long as one word of a topic appears in a summary, the corresponding movie is considered to belong to this theme. The number of topics per year can be computed and can be related to the number of fictional movies released in the same time period. The results are shown on the plot below. A topic curve (blue) above the total fictional movies curve (yellow) means that the specified topic is more represented on the period and vice versa.

Sentiment Analysis

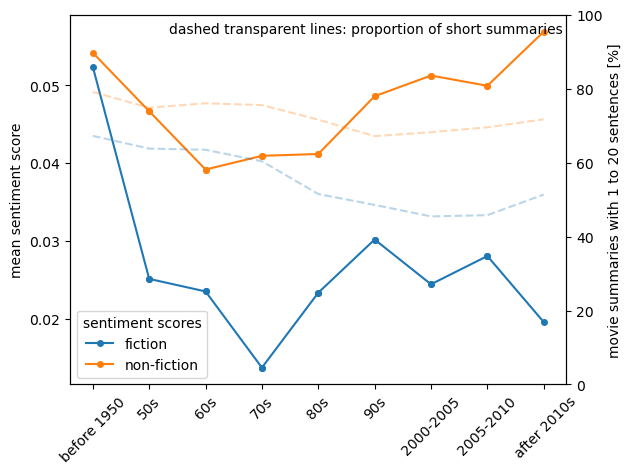

In the previous sections we learned a lot about how fictional worlds are portrayed by analyzing the topics of fictional movies. Through this, we also saw how the interest of people changed during the last century. But what feelings were conveyed by these fictional movies? To answer this question, we perform sentiment analysis on the movie summaries. First we look at the sentiment of fictional movies compared to non-fictional movies:

As we can see, fictional movies generally have a lower sentiment score when compared to non-fiction while still being above the neutral score of 0. This could mean that people like to imagine that things are worse than what is observed in reality.

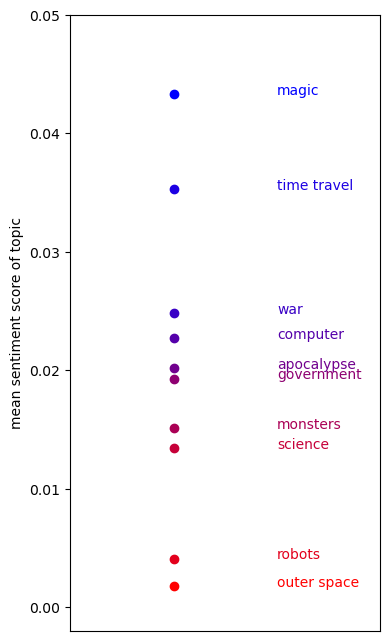

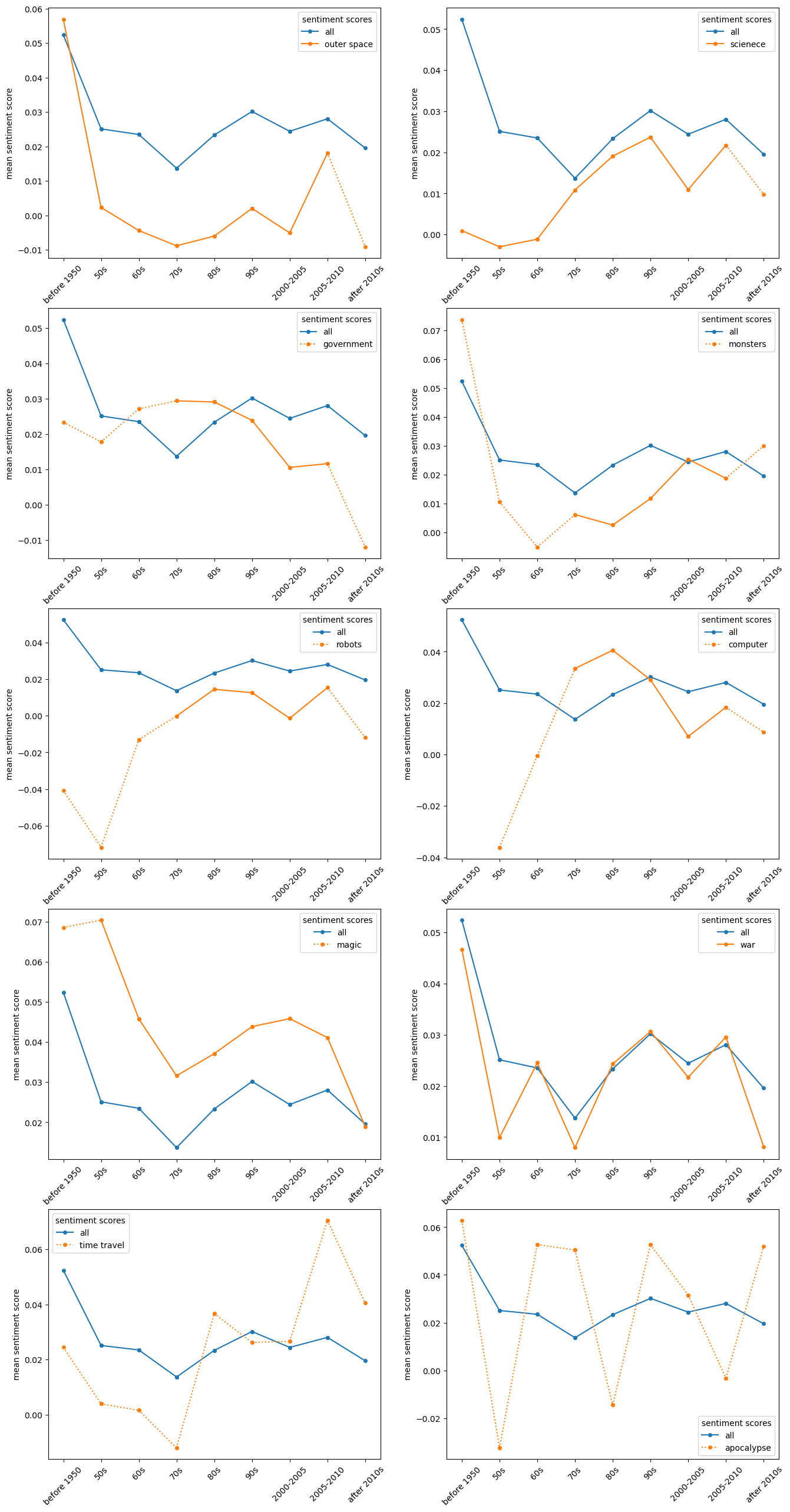

Comparing the sentiments of different topics of the previous analysis gives us an idea about the perspective people had on things. To do this, the average sentiment scores of every movie summary for each topic is plotted below.

If we take a look at the sentiment of different topics, we see that movies with the topic magic have the highest sentiment score, followed by time travel. Certainly, magic and time travel would be highly convenient and seem to make life easier! Surprisingly, war movies do not have particularly low sentiment scores. On the other hand, movies about robots and outer space scored the lowest. When thinking about the vast amount of alien invasions or the classic movie ‘terminator’ this does seem to be plausible.

To get indications for why certain topics scored low and others high and how their scores changed over time, we visualize the evolution of sentiment scores of all topics. In the plots, dashed lines indicate that the datapoint following the dashed line is computed with a low number of summaries and their value should be interpreted as highly uncertain.

Unfortunately, the dataset used did not contain enough summaries to plot meaningful evolutions of sentiment for all topics. Nevertheless, we can extract some interesting information. Movies about outer space started with a high sentiment score and decreased during the period of the cold war. This seems to be unusual, because one would expect a lot of inspirational movies about space exploration during the space race successive moon landing of the americans. Science movies started with low sentiment scores which gradually increased over time. Was science associated with hazards in earlier years? Sentiment scores of war movies follow the average score consistently, most likely due to a large number of fictional movies being war related. A dip for movies in the 50s can be related to the cold war. Just like in the direct comparison of topic sentiments, magic movies score high. The difference to the average sentiment of fictional movies does not change over time. So apparently magic really does make things just slightly better. What a shame that this topic is speculative fiction!

Conclusion

Our dive in people’s imagination comes to an end.

We dealt with a small fictional movie summary sample containing mainly recent creations from northern america and europe, not encompassing the vastness of human imagination.

However, while trying to avoid as many pitfalls as possible, it has been possible to emphasize several fiction themes and their evolution over time. We saw the emergence of themes related to computers, confirmed the uprising of outer space related movies at the dawn of space exploration and we observed the fascination people have for magic. Imagination is an extension of reality!